—for my mother, Beverly Ann (Lusk) King, 1932-2018

My mother was the eleventh child of fifteen children, and the tenth daughter of twelve daughters. Although her family had a camera, and other families from this era are well-documented, we have only nine photographs of her as a child, and only a few of them feature her by herself.

In the earliest photograph documenting my mother’s childhood, she is held by her two eldest sisters, Rayma and Oretta. They stand against a backdrop of trees. It looks to be spring. As she was born in October, that makes her five or six months old. Rayma and Oretta had named her “Beverly Ann.” At the time of the photograph, they were nineteen and twenty. Within the year both had married and left home.

My grandparents, Wert and Arada, called Rady, named very few of their children. Oretta was called “Babe” until daughter number six came along. Then Oretta was “Big Babe,” and she-who-would-eventually-name herself, Minnie Jane, was “Little Babe.”

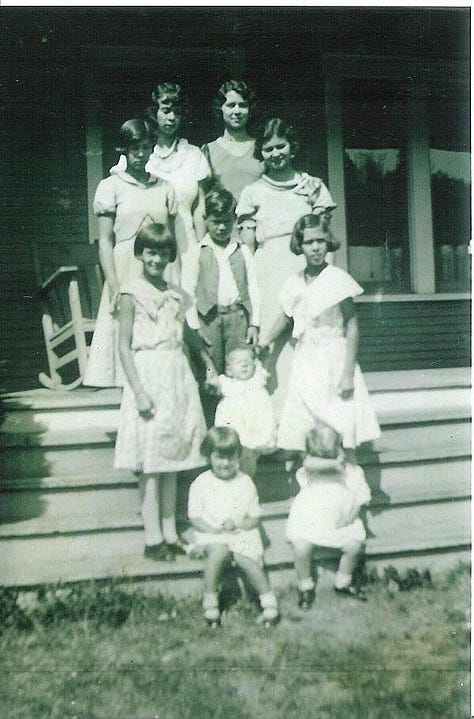

In the second photograph of my mother, she stands with her older siblings on the front steps of their house. Nine girls, one boy. The boy, my uncle Buck (Wert Junior), and my mother, the baby, are framed by the others. Two of the sisters hold little Beverly up by the hands, as she appears to be too young to stand independently of help.

In the next photograph, my mother is a toddler in a white dress. She stands alone on the grass, barefoot, looking up unhappily as if to say, “Please pick me up.” There is no photographic evidence that her mother ever held her, though it must be assumed she did, at least as an infant. To be fair, except for a studio portrait of my grandparents with their two oldest daughters, I can’t recall any photographs of my grandmother with a baby on her lap, not until grandchildren came along, or maybe great-grandchildren when the “generations” photos began.

My mother was four years old when someone snapped a photograph of her and four other close-in-age children. Two are her sisters. The others are their oldest niece and nephew. My mother had brown eyes and brown hair, but in this photo, her hair appears to be blonde, like mine. There is something about her face in this photograph, too, that makes me recognize my features in hers.

Around the ages of seven and eight, my mother was captured in two school photographs. In the earlier one, her dark hair is in a straight bob with bangs, parted in the middle. In the second photograph, her bangs are pinned to one side and her hair is in curls, which means her older sisters had begun taking her to the local grange to have her hair permed. “A completely normal thing to do.” From that time on, Mom always had permed hair, except for when she had chemotherapy at age 55, for breast cancer, and after she moved into a nursing home, at 82. The stylist who worked at Mom’s care home said she was happy to keep it permed, but the first attempt was too much like torture.

The next photo skips to age thirteen or fourteen. My mother stands beside her sisters Donna and Darlene. Donna is eleven months older, and Darlene is two years younger. Donna and my mother were “outside girls,” meaning their daily chores were at the barn. They threw hay down for the cattle, mucked out the manure trough, milked cows, and fed calves from a pail. In summers, they worked alongside their father and brothers-in-law, harvesting hay. Older sisters had once had this same designation, “outside girls,” but it was now the post-war years. Times had changed. Donna and Beverly complained about wearing dresses for their chores, and their father drove them into town to J. C. Penney or Monkey Wards where they bought denim jeans and tee shirts. I asked Mom why Darlene, who was an “inside girl,” was included, and Mom said, “Because she whined to Mother.”

In a second photograph taken that day, Mom crouches beside their dog, Shep. Shep looks to be a shepherd mix. Mom’s long brunette hair curls over her shoulders. She is smiling. She was more than an outside girl, of course. As a teenager, she taught herself to play piano and guitar. Also, accordion, though she once told me, “Anyone can play the accordion.” Her father bought her a guitar. She had a fine tenor voice and sang as part of a trio at the Doty Pentecostal Church of God. She had a boyfriend named Eddie who was the son of a minister. We have one photograph of Eddie, wearing a wide-brimmed cowboy hat and sitting on a horse.

Finally, we have a studio portrait of—in my family’s vernacular—“the whole fam damily.” It is black and white but color-tinted. Here, my mother is fifteen years old, seated in the front row between her younger brother Ronnie, eight years old, and their father. The girls, except for the youngest, wear white blouses. Their hair is permed and henna-ed, or looks to be. Mom’s one older brother, Buck, stands in the middle of the back row, wearing a black sweater, looking like an outlaw. The two youngest children, Bunny and Billy, probably six and four years of age, wear blue. This photograph appeared in the Vail-MacDonald section of Weyerhaeuser Magazine in April of 1953, with a two-page article, “Record Family.” When I was a child, the portrait hung, framed, on the wall of almost every living room I knew. It seemed a standard issue, like upright pianos.

At twenty my mother met my father, a man who owned two cameras and had darkroom equipment for developing photographs. It was a whirlwind courtship. Photographed wrapped in his arms, singled-out, adored, she looks as though she is swooning.

Bethany Reid’s fourth full-length collection of poems, The Pear Tree: elegy for a farm, won the 2023 Sally Albiso Award from MoonPath Press. A former poetry editor of Seattle Review, she leads a writing workshop, teaches for the Creative Retirement Institute (CRI), and blogs about writing and life at http://www.bethanyareid.com